What I discovered about the friendship of St. Luke and St. Paul

Jim Caviezel (l) portrays St. Luke in Paul, Apostle of Christ,

which also stars James Faulkner (r) in the title role.

Reel Presence: How Friendship

is a Synonym for Salvation

„Baptism and the Eucharist are now the means by which men and women are

incorporated into God’s covenant family. They mark the Christian’s covenant oath, common meal, and sacrifice. The word “sacrament” itself witnesses to this truth.

‘Sacrament” comes from the Latin sacramentum, which means “oath,” and the word

was applied to Baptism and the Eucharist from the earliest days of the Church.

The pagan Roman governor Pliny the Younger recorded that Christians in his time (the end of the first century) would gather before sunrise to sing hymns to Christ, after which they would “bind themselves by an oath.’ This is the sacramentum, the oath, which seals the

covenant: the Holy Eucharist. Jesus Himself described His relationship with the Church in explicitly covenantal terms. At the Last Supper, He blessed the cup of the new covenant in

His Blood (cf. Mt. 26:28; Mk. 14:24; Lk. 22:20; 1 Cor. 11:25). This makes a big difference in our life; for now, as Christians, we can call God ‘Abba! Father!’ (Gal. 4:4–6). We are truly children of God (cf. Jn. 1:12; 1 Jn. 3:1–2), brothers and sisters and mothers of Christ (cf. Mk. 3:35), Who is the ‘first-born among many brethren’ (Rom.8:29). Christians are ‘members of the household of God’ (Eph. 2:19). The primary revelation of Jesus Christ

is God’s fatherhood (cf. Jn. 15). Jesus reveals God first as Father to Himself, and then,

by extension, to Christians, as ‘sons in the Son’. . . “ — From „Scripture Matters“

Scripture Matters: Essays on Reading the Bible from the Heart of the Church.

Dr. Scott Hahn: A Presbyterian Minister Who Became a Catholic – The Journey Home

Predigt vom 17.07.2022 – Eine siebenfache Einladung zum Glauben

6. Das Tochtersein bei Jesus

Stehe an der Spitze, um zu dienen, nicht um zu herrschen.

Bernhard von Clairvaux

say is true about God really is true, not just a warm personal sentiment or a peculiar family tradition. It requires that we honor Him as if He really is our Creator and sustainer, cleave to the Church as if her sacraments were really efficacious, and love God and our neighbor as if grace really can elevate and perfect every bit of our soul. When we do this—when we live the fullness of truth in justice to God and man—we reveal the civilization of love not just as a possibility but as the deep reality of creation itself. We have been brought into being and are sustained in being by the God who is Love. Therefore, love is not the exception, not a foreign input to an otherwise sterile cosmos; love is the very grammar of existence that

gives meaning, rooted in Jesus Christ, to everything we see and hear and touch.

Without love, we are nothing (see 1 Cor 13:1–3). With love, which includes doing justice

to God through the virtue of religion, our souls and our civilization can be more beautiful

than anything our secular, idolatrous, nihilistic culture can imagine. . .

– From “It Is Right and Just” Available at https://bit.ly/2GtpyVq

disciples, “I will not leave you orphans” ( Jn 14:18). Some translations render the last

word as “desolate,” but the Greek word is orphanous, which means, literally, a child with-

out either father or mother. In the ancient world, orphans were those who had no family to care for them, no place to live. They were desolate, outcast by circumstance, the poorest of the poor. Since Jesus was going away, He knew the anxieties His disciples would feel.

For three years, He had been family to them—a father figure, a patriarch, an elder brother.

He wanted to assure them that He would not leave them homeless or without a family. . .

– From “First Comes Love” Available at http://bit.ly/2WVUD6q

We’re to live as His children, “chosen ones, holy and beloved,” as the First Reading puts it.

is all solid and practical. Happy homes are the fruit of our faithfulness to the Lord, we sing in today’s Psalm. But the Liturgy is inviting us to see more, to see how, through our family obligations and relationships, our families become heralds of the family of God that He wants to create on earth.

Read more of my reflection on the Feast of the Holy Family at https://bit.ly/3e9JQkh

Whom He dared to call “Father.” For Jesus, God is not “father” in a metaphorical sense.

Nor is God “father” to Jesus merely through the act of creation. On the contrary, Jesus’

sonship is something real, unique, and personal (see CCC, no. 240). God, to Jesus Christ,

is “Abba”—which means “Daddy” or “Papa” (see Mk 14:36) …

In Israel, the Twelve Tribes understood themselves collectively to be the “Family of God,” but in something more than a metaphorical sense, because God created them, guided them, protected them, and provided for them—as a father begets, guides, protects, and provides for his family. God, then, acted as a father to the nation of Israel (see Dt 32:6;

Jer 31:9). Individually, however, Israelites tended to refer to themselves not as God’s

children, but as His “servants” or “slaves” (see, for example, 1 Sm 3:9 and Ps 116:16).

Even the greatest of the patriarchs, Abraham, could be called God’s “friend” (Is 41:8),

but not His son. . .

— from my book “First Comes Love” at bit.ly/2WVUD6q

Why on earth would anyone choose celibacy?

with close family members wherever they go, at work and at leisure. They are single not

because they haven’t found a family. They are single as a way of living family life.

Their single state enables them to do God’s work and to reach people they could not otherwise reach. If their single state isn’t vowed and permanent, it’s at least providential and present—and it provides them no less an opportunity for total self giving than married life gives to spouses. Celibacy—the vowed and permanent single state—is not a repression

of the natural. It is, rather, a fulfillment of the natural desires by supernatural means.

God made marriage, after all, to be a means to heaven. Yet Jesus says that, in heaven, people “neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like angels” (Mk 12:25).

The celibate chooses to live, right now, as if he or she were already in heaven with God.

As Jesus put it, consecrated celibates have “made themselves eunuchs”—that is, they have voluntarily renounced sexual activity—“for the sake of the kingdom of heaven” (Mt 19:12).

The drive to procreate joyfully sacrificed, is made sublime and turned into a zeal to win souls for God’s covenant family. Jesus Himself promised that this would happen:

“Truly, I say to you, there is no man who has left house or wife or brothers or parents or children, for the sake of the kingdom of God, who will not receive manifold more in this time, and in the age to come eternal life” (Lk 18:29–30).

First Comes Love: Finding Your Family in the Church and the Trinity

The Hebrew word for holiness is kiddushin, which also means marriage. When something is holy, it is consecrated, set apart from everything else—in that sense, it is transcendent. Yet it is set apart, not for isolation, but for a personal and interpersonal purpose; not for distance, but for intimacy. In the ancient world, this consecration was achieved by means of a covenant. More than a contract, more than a treaty, a covenant created a family bond between persons or between nations. A wedding took the form of a covenant oath; so did the adoption of a child or the naming of a newborn. These new family relationships brought with them certain privileges and duties. The parties of a covenant invoked God’s name as they swore to fulfill their responsibilities. Should they fail, they accepted the most dire penalties, because they had placed themselves under God’s judgment. By entering into a covenant relationship, they were, in effect, calling down a blessing or a curse (cf. Deut. 11:26). If they were faithful, they would receive God’s blessing. If they were unfaithful,

they drew down their own curse.

God’s name itself served as an oath. To invoke His name was to call upon Him and place oneself under His judgment. The name of God is the power behind the covenant.

The name of God, then, is His own covenant identity, His personal identity. It’s what proves our personal relationship with Him. When we call upon that name—“Our Father!”—

God responds as a Father, and we receive His help. We also bring on His judgment, but that judgment is a blessing to those who avail themselves of His help. When Jesus teaches us

to pray, “Hallowed be thy name” (Mt. 6:9), He shows us that the name of God is consecrated. It is holy. God’s name is not merely transcendent and mysterious; it is intimate and

personal and interpersonal. It is the basis for the covenant.

—from my book, “Understanding Our Father” at bit.ly/2RDX52N

the family. In the ancient Near East, a covenant was a sacred kinship bond based on a

solemn oath that brought someone into a family relationship with another person or tribe. When God made His covenants with Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, and David, He was

gradually inviting a wider circle of people into His family: first a couple, then a family,

then a nation, and eventually the world. All of those covenants failed, however, because of man’s unfaithfulness and sin. God remained constantly faithful; Adam did not, and neither did Moses, neither did David. In fact, sacred history leads us to conclude that only God keeps His covenant promises. How, then, could mankind fulfill the human end of a covenant in a way that would last forever? That would require a man to be sinless and as constant as God. Thus, for the new and everlasting covenant, God became man in Jesus Christ, and He established the covenant by which we become part of His family: the family of God.

This means more than mere fellowship with God. For “God in His deepest mystery is …

a family.” God Himself is Father, Son, and the Spirit of Love—and Christians are drawn up

into the life of that family. In baptism we are identified with Christ, baptized in the Trini-

tarian name of God; we take on His family name, and thus we become sons in the Son.

We are taken up into the very life of the Trinity, where we may live in love forever.

If God is family, heaven is home; and with Jesus, heaven has come to earth. . .

– From “Hail Holy Queen” Available at https://goo.gl/bNjMB3

in danger of giving up waiting and putting its trust in doing, which—indispensable as it is—can never fill the void that threatens man when he does not find that absolute love which gives him meaning, salvation, all that is truly necessary in order to live.“

Joseph Ratzinger, „Introduction to Christianity“

of our natural families? Quite simply, we are to make them heaven. To become all that God has made us to be, we must grow ever more perfectly in His divine image. That means we must give ourselves completely. Now, except in the extraordinary case of martyrdom, we cannot do this all at once—and we can never do it alone. We grow perfect in the image of God only as we “become Christ,” in communion with Christ and in communion with others, in communion with the Church. Where does this begin? It begins, ordinarily, in our natural families, which God intends to be the fundamental unit of the Church. The Church and the family are more than “communities”; each is, like the Trinity, a communion of persons.

And so they also bear a family resemblance to one another. As the Church is a universal

family, the individual family is “the domestic Church” (see CCC, no. 1656).

new family resemblance to God. St. Paul wrote, “For this reason I bow my knees before

the Father, from Whom every family in heaven and on earth is named” (Eph 3:14–15).

Earthly families, then, receive their “name,” their identity, their character, from God

Himself. They are made in His image.

— from my book “First Comes Love” at bit.ly/2WVUD6q

Scott Hahn has the rare ability to explain the essential teachings of Catholicism in a totally accessible manner. Rather than burdening the reader with difficult or arcane references and arguments, he writes of familiar feelings and situations and allows the theology to

unfold naturally. In First Comes Love, Hahn turns his attention to the search for a sense of

belonging, revealing the intimate connection between the families men and women create on earth and the divine family, the Holy Trinity.

Delving into the Gospels, Hahn shows that family terminology—words like brother, sister,mother, father, and home—dominates Jesus’ speech and the writings of His first followers, and that these very words illuminate Christianity’s central ideas. As he explores the fatherhood of God, the marriage of the Church to Christ, and the all-enveloping role of the Holy Spirit, Hahn deepens readers’ understanding of the sacraments, teaches them how to create a family life in the image of the Trinity, and demonstrates the ways in which the analogy of the family applies to every aspect of Catholicism and its practices—from the role of “father” embodied by the ancient patriarchs and contemporary parish priests, to the comfort and guidance offered by the brothers and sisters who comprise the Communion of Saints, to the nurturing embrace of Mary, the mother of all Christians.

Through real-life examples (both humorous and compassionate) and quotations drawn from the Scriptures, Hahn makes it clear that no matter what sort of family readers come from—no matter what sort of “dysfunction” they have experienced—they can find a family in the Church. Reaching out to newcomers and to lifelong Christians alike, First Comes Love is an invitation to discover a true home in the divine.

guardian angels and St. Michael, too. We should know their presence, as Saints Peter and Paul did in the Acts of the Apostles. And we should speak with them, as St. John did in the Book of Revelation, and as the prophets did in the Old Testament. We may do this silently, in our souls. We are spiritual beings as the angels are, and we can communicate with

them through the ways of prayer.

our relationships. We can make them our partners in a holy conspiracy as we try to draw friends and neighbors and co-workers into a deeper life of faith. It was customary, through most of the twentieth century, to invoke St. Michael’s help at the end of every Mass.

Congregations prayed the prayer promoted by Pope Leo XIII at the end of the nineteenth century—a prayer he composed, reportedly, after an extraordinary and ominous vision

of spiritual warfare as it would unfold in the coming years.

The Church celebrates the feast of St. Michael and All Angels on September 29 and the feast of the Guardian Angels on October 2. We have a lot to celebrate on those days. By God’s design, the angels are active in our life, from the time we are conceived to the moment of our earthly end. Our moments go better if we work with the angels, as the Scriptures show!

—from my book “Angels and Saints” at bit.ly/2WSJ7Zx

As He hung dying on the cross, in His last will and testament, Jesus left us a mother.

“When Jesus saw His mother and the disciple whom He loved standing near, He said to His mother, ‘Woman, behold, your son!’ Then He said to the disciple, ‘Behold, your mother!’ And from that hour the disciple took her into his home” (Jn 19:26–27). We are His beloved disciples, His younger siblings (see Heb 2:12). His heavenly home is ours, His Father is ours, and His mother is ours. Yet how many Christians are taking her to their homes? Moreover, how many Christian churches are fulfilling the New Testament prophecy that “all generations” will call Mary “blessed” (Lk 1:48) Most Protestant ministers—and here I speak from my own past experience—avoid even mentioning the mother of Jesus, for fear they’ll be accused of crypto-Catholicism. Sometimes the most zealous members of their congregations have been influenced by shrill anti-Catholic polemics. To them, Marian devotion is idolatry that puts Mary between God and man or exalts Mary at Jesus’ expense. Thus, you’ll sometimes find Protestant churches named after Saint Paul, Saint Peter, Saint James, or Saint John—but rarely one named for Saint Mary. You’ll frequently find pastors preaching on Abraham or David, Jesus’ distant ancestors, but almost never hear a sermon on Mary,

without calling her at all. This is not just a Protestant problem. Too many Catholics and

Orthodox Christians have abandoned their rich heritage of Marian devotions.

They’ve been cowed by the polemics of fundamentalists, shamed by the snickering of

dissenting theologians, or made sheepish by well meaning but misguided ecumenical

sensitivities. They’re happy to have a mom who prays for them, prepares their meals,

and keeps their home; they just wish she’d stay safely out of sight when others are

around who just wouldn’t understand.

—from my book “Hail, Holy Queen” at bit.ly/2OvkBLZ

very distinctive forms of exchange. A contract is the exchange of property in the form of goods and services (“That is mine and this is yours”); whereas a covenant calls for the

exchange of persons (“I am yours and you are mine”), creating a shared bond of inter-

personal communion. For ancient Israelites, a covenant differed from a contract about as much as marriage differed from prostitution. When a man and woman marry, they declare before God their undying love to one another until death, but a prostitute sells her body

to the highest bidder and then moves on to the next customer. So contracts make people customers, employees, clients; whereas covenants turn them into spouses, parents,

children, siblings. In short, covenants are made to forge bonds of sacred kinship.

Scripture reveals how God has used covenants to forge family bonds with his people in every age. This is echoed in the common formula used throughout Scripture to describe God’s covenant bond with us: “I will be their God, and they shall be my people.…

I will be a father to you, and you shall be my sons and daughters” (2 Cor 6:16–18).

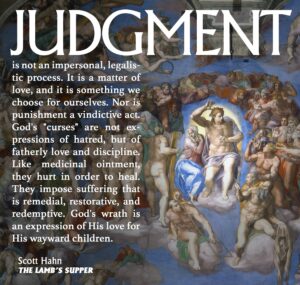

Of course, the climax of the process is the New Covenant, when Christ opened up the inner family life of the Trinity for all of us to share. So if you want to get to the heart of Scripture, think covenant not contract, father not judge, family room not courtroom; God’s laws and judgments are meant to be interpreted as signs of his fatherly love, wisdom and authority. This does not imply a lower or less strict standard of justice, however, since a good father requires more from his son than the judge expects from a defendant, or the boss from his employee. The terms of a covenant call for certain actions to merit rewards or benefits, while a breach of the commitment results in specific penalties and damages. This follows the pattern of family life, where children work to get an allowance, and when they grow up and prove their maturity, they can reasonably expect to be rewarded with an inheritance.

However, if they persist in serious sin, they face the prospect of disinheritance.

This is the biblical pattern of the covenant as well, for the Father blesses his children when they keep the covenant, just as he punishes them for breaking it. All of this is spelled out in the covenant, in terms of blessings and curses (see Dt 28). The blessings mean life, while the curses mean death; so God urges his people to choose life and behave in such a way

as to enjoy his fatherly blessing.

—from my book “A Father Who Keeps His Promises” at bit.ly/2M88vtj

History unfolds, in Revelation, as a series of covenant blessings and curses. John portrays earthly destruction in terms of a terrible Passover. Seven angels pour out the seven chalices of God’s wrath, which issue in seven plagues. The emptying of the chalices is a liturgical action, a libation of wine poured upon the land. (Indeed, both sevens and liturgical images abound in Revelation: There are seven golden lampstands, seven spirits, seven stars, seven churches, seven seals, seven trumpets, and seven chalices—to name just seven.)

setting: The angels appear with harps, vested as priests in the heavenly Temple;

they sing the song of Moses and the song of the Lamb (ch. 15). This liturgy means death to God’s enemies, but salvation to His Church. Thus, the angels cry: “For men have shed the blood of saints and prophets, and You have given them blood to drink. It is their due!”

(Rev 16:6). Passover, the Eucharist, and the heavenly liturgy, then, are two-edged swords.

While the chalices of the covenant bring life to the faithful, they mean certain death to those who reject the covenant. In the New Covenant, as in the Old, God gives man the choice between life and death, blessing and curse (see Dt 30:19). To choose the covenant is to choose eternal life in God’s family. To reject the New Covenant in Christ’s blood is to

choose one’s own death.

– From my book “Swear to God” Available at https://bit.ly/3eqrGeI

assume that it’s not Peter, but rather his angel (12:15)!

angels. So do our lives. The early Christians knew this. That’s why they could easily mistake a man for his guardian angel. Since Peter was imprisoned, they would naturally be surprised to find him at the door, but they were not surprised to encounter his angel!

We need to have such faith and such a lively awareness of our guardian angels.

For God has given us—each of us—the same powerful heavenly guidance, protection, and assistance. Devotion to the angels did not arise as something new with the proclamation

of the Gospel. It has always been a part of biblical religion. Angels fill the Bible, from beginning to end, Genesis to Revelation. They are key players in the drama of the Garden of Eden. They appear frequently in the life of the patriarchs: Jacob even wrestles with one. They go before the Israelites during the exodus. They deliver God’s word to the prophets. The prophets themselves reveal that even nations have guardian angels. The book of Tobit shows us how an angel guided a young man to recover his family’s fortune, discover a cure for his father’s blindness, and find a beautiful and virtuous wife along the way!

The New Testament opens with an explosion of angelic activity. Neither Joseph nor Mary seems particularly surprised to receive the help of angels.

—from my book “Signs of Life” Available at bit.ly/36hUEY9

lives, in history, and in the spinning out of the cosmos. Indeed, little things matter so much to us because they matter so much to God. That is the plain meaning of Jesus’s parable of the talents (Matthew 25:14–31)—a parable of ambition. Twice in that parable Jesus portrays the master (representing God) as saying, “Well done, good and faithful servant;

you have been faithful over a little, I will set you over much; enter into the joy of your

master.” It’s the little things that count, even for God. For in our attention to little things,

we imitate Him most perfectly. Our God is the master of the universe, whose mind and power are evident in the formation of the Himalayas, but also in the movement of subatomic particles.And He doesn’t move mountains without moving a whole lot of electrons

in the process!

A quote from my book “Ordinary Work Extraordinary Grace”, available at bit.ly/2WcM1bn

—from my book “Ordinary Work Extraordinary Grace” at bit.ly/2WcM1bn

prayer. Even St. Paul felt the force of the problem with all his heart and mind. He called it the “mystery of iniquity” (2 Thess 2:7). It is a mystery, something hidden even from so great a saint. Why is there evil if God is both all-powerful and all-good? If He is all-good, His creation should reflect that perfection. If He is all-powerful, then He should be able to prevent evil from happening. Yet we cannot solve the problem by dismissing God. In fact, such a denial only makes the problem worse. Denying God’s existence in order to solve the problem of evil is like burning your house down in order to get rid of termites, or cutting off your head to stop a nosebleed. People who allow evil to drive them to atheism suddenly have no standard by which to judge something evil. Instead of solving the problem, they’ve institutionalized it—written it into the very fabric of the cosmos. If there is no God, then there is no transcendent, ultimate goodness, no perfect measurement

or mere human preference. . .

—from my book “Reasons to Believe” bit.ly/2LutweV

Wir müssen nicht denken, dass unsere Liebe außergewöhnlich zu sein hat. Aber dennoch müssen wir lieben ohne müde zu werden. Wie brennt eine Öllampe? Durch einen ständigen Tropfen Öl, der nachfließt. Diese Tropfen sind wie die kleinen Dinge des alltäglichen Lebens: Treue, kleine freundliche Worte, eine Kleinigkeit, die dem anderen zeigt, dass wir

an ihn dachten, die Art und Weise wie wir miteinander still sein können, wie wir schauen, sprechen und uns verhalten. Dies sind die wahren Tropfen der Liebe, die unsere Leben

und Beziehungen am Leuchten halten wie eine kleine lebendige Flamme.

Mutter Teresa (1910 – 5. September 1997)

of human life. He waits for us every day, in the laboratory, in the operating theatre, in the

army barracks, in the university chair, in the factory, in the workshop, in the fields, in the home and in all the immense panorama of work. Understand this well: there is something holy, something divine, hidden in the most ordinary situations, and it is up to each one

of you to discover it.

—from my book “Angels and Saints” at bit.ly/2WSJ7Zx

Sollen wir unseren Vater nicht mehr Vater nennen?

Wie war der Kontext? Hat Jesus vor Familien gepredigt und ihnen Hinweise auf die Ansprache der Eltern gegeben? Nein. Jesus sprach über das Verhalten der religiösen Führer und kritisierte sie. Konkret sagte Jesus zu den selbstgefälligen Religionsführern:

„Ihr aber sollt euch nicht ›Meister‹ nennen lassen; denn einer ist euer Meister, ihr alle aber seid Brüder. Und niemand auf Erden sollt ihr euren ›Vater‹ nennen; denn einer ist euer Vater, der im Himmel. Auch ›Lehrer (oder: Führer)‹ sollt ihr euch nicht nennen lassen; denn einer ist euer Lehrer (oder: Führer), nämlich Christus. (Jesus in Matthäus Kapitel 23, Verse 8-10)

Gott und Jesus würden uns niemals dazu auffordern, innige Bande zu anderen Menschen, insbesondere zu Vater und Mutter aufzukündigen. Im Gegenteil, wir sind von Gott aufgefordert, unseren Vater und unsere Mutter zu ehren: „Ehre deinen Vater und deine Mutter,

damit du lange lebst in dem Lande, das der HERR, dein Gott, dir geben wird!“

(Exodus / 2. Mose Kapitel 20, Vers 12; Menge Bibel, 1939)

Beim Lesen der Bibel müssen wir also auch immer auf den Kontext achten. Wann hat wer zu wem gesprochen? In diesem Fall sprach Jesus über das von ihm kritisierte selbstgefällige Verhalten der Religionsführer (die übrigens später seinen Tod von der römischen

Besatzungsmacht forderten). Was wollte Jesus damit sagen? Wahre Autorität liegt bei Gott; nicht bei organisierter Religion. Wenn Jesus sagt(e), man solle religiöse Führer nicht als ‚Vater‘ ansprechen, dann ist damit gemeint, daß wir niemanden hier auf Erden die spirituelle Autorität geben sollen, sondern nur unserem uns liebenden himmlischen Vater.

Jesus sprach in Matthäus Kapitel 23, Verse 8-10, über religiöse Dinge, nicht über leibliche

Bindungen, die in Exodus 20:12 (Ehre deine Eltern) das Thema sind.

Some people say that Jesus was using the bread and wine as metaphors to explain His upcoming sacrifice. But, if that were the case, they would be useless. They fail as metaphors, because it is the bread and wine and not His death that require explanation! Jesus’ words are not so much an explanation or a teaching as a “speech-act,” a declaration that brings about what it expresses—like “Let there be light” or any of God’s covenant promises.

Jesus’ speech does not come after the event; it brings about the event. So what is implicit at the Last Supper becomes explicit in the Emmaus story, where the visible presence of the Lord vanishes during the distribution of the pieces (24:31). Why did this happen?

Because, in light of Luke 22:19, His presence was now identified with the bread.

Thus the messianic king was “made known” to the disciples “in the breaking of bread” (24:35). Later, Luke links his own liturgical experience to Jesus’ Last Supper by including himself among those who gather on the first day of the week to “break bread” (Acts 20:7).

In the Last Supper and the Emmaus story, Christians—throughout all of history—

have learned that the risen Christ is truly present in the bread we break together.

—from “Reasons to Believe” at

Reasons to Believe: How to Understand, Explain, and Defend the Catholic Faith

-from “Understanding Our Father”

Understanding “Our Father”: Biblical Reflections on the Lord’s Prayer

If the second greatest commandment—“You shall love your neighbor as yourself”

(Mt 22:39)—means anything at all, it means that we are to value the good of others no less than we value our own good. This means that we must do more than just act independently for the private good of ourselves and those closest to us; we must work to form a society ordered to the common good of all. Remember that when the lawyer challenged Jesus by asking, “And who is my neighbor?” He responded with the parable of the Good Samaritan (Lk 10:25–37).

The late and eminent St. Thomas Aquinas scholar Charles De Koninck pointed out in his On the Primacy of the Common Good that in the same way that our love of particular persons proceeds from our love of God, our love for particular goods—that is, the good of particular persons and communities—proceeds from our love for greater, more universal goods.

God is Himself the universal good of all creation, and we therefore love this good most of all. This means, then, that we are to love and to pursue the common good of society more than any particular good, because those particular goods proceed from the common good.

— from my book „The First Society“ at

The First Society: The Sacrament of Matrimony and the Restoration of the Social Order

Koexistenz setzt Existenz voraus in Interview, Melchior Nr. 13

Der französische Philosoph Rémi Brague im Gespräch

über Politik, Werte und das Zusammenleben in Familie und Staat.

Eine Gemeinschaft ist also auf der einen Seite das Elementarere und Humanere im

Vergleich zur Gesellschaft. Auf der anderen Seite aber vielleicht das Schwierigere.

Corruptio optimi pessima. Diesen lateinischen Spruch kennt man: „Das Verderben der Besten ist das schlimmste Verderben.“ Deswegen ist es im ganzen Verlauf der Geschichte schwierig, echte Politiker im edelsten Sinne des Wortes ausfindig zu machen.

Meiner Meinung nach lassen viele ein notw. Gefühl für die Würde des Amtes vermissen.

Die Familie ist aber keine politische Zelle im eigentlichen Sinne, da muss man aufpassen. Das politische Leben richtet sich, genauso wie das wirtschaftliche Leben, an der Idee der Leistung aus. Ich leiste etwas und bekomme als Gegenleistung etwas: Geld, Ehre oder was weiß ich. Dabei ist die große Gefahr in unserer Gesellschaft, dass man den Menschen auf seine Leistungsfähigkeit reduziert. In der Familie hingegen hat jedes Kind eine Würde,

ganz abgesehen von seiner Leistung… Daher existiert ein unvermeidlicher Konflikt

zwischen Familien und politischem Leben.

Jesus lehrte seine Jünger, Gott als Vater anzusprechen.

Manche Theologen halten diese Anrede für den Ausdruck eines überholten patriarchalischen Weltbildes und ergänzen die männliche Anrede Gottes durch weibliche Anreden z.B. in Bibelübersetzungen, in Liturgien oder Predigten: „Du, Gott, bist uns Vater und Mutter

im Himmel.“ Doch ist es gerechtfertigt, Gott als Vater und Mutter anzusprechen?

Die Vater-Anrede des Vaterunsers geht zurück auf die Selbstoffenbarung Gottes als Vater

an sein Volk: Israel ist Sohn Gottes (2. Mose 4,22; 5. Mose 14,1; 32,6; Hos 11,1), die sich in

der Vater-Anrede der Propheten u. der Psalmen an Gott fortsetzt (Jes 63,16; 64,8; Jer 3,19; 31,9; Mal 1,6; 2,10; Ps 68,6; 103,13).[1] Und sie wird weitergeführt und entfaltet in der

Anrufung des Vaters durch seinen Sohn Jesus Christus (etwa Joh 20,17) und im Gebet der Kinder Gottes. Fast alle Briefe des Neuen Testaments beginnen damit, etwa in Röm 1,7: „Gnade sei mit euch und Friede von Gott, unserm Vater, und dem Herrn Jesus Christus“.

Allein im Neuen Testament wird „Vater“ ca. 250mal auf Gott bezogen (besonders häufig

bei Joh).Wenn Jes 66,13 das göttl. Erbarmen mit dem Erbarmen einer Mutter vergleicht, dann ist das ein Vergleich, aber keine Seinsaussage: Er kann sich wie eine Mutter erbarmen, aber er ist von Ewigkeit her Vater, zunächst zu seinem einen Sohn, dann zu den vielen Söhnen und Töchtern in seinem Volk. Er zeugt durch das Wort (der „Same“ des Glaubens, 1. Petr 1,23). Und was Jes 66,13 betrifft: Der Herr tröstet, wie einen seine Mutter tröstet, sein Mittel dazu aber ist Jerusalem: „an Jerusalem werdet ihr getröstet“ schließt der Vers. So dürfen auch wir glauben: Was Gott an Israel tat und tut, und was er an seiner Gemeinde tat und tut – daß sie etwa nicht einmal von den Pforten der Hölle überwunden werden kann –, das ist der große Trost für seine Gläubigen. Die biblische VATER-Offenbarung steht in einem unüberbrückbaren Gegensatz zu den antiken Schöpfungsmythen. Diese leiten

die Existenz der Erde häufig von weiblichen Gottheiten ab. Meist waren es Naturgottheiten, symbolische Repräsentationen der geheimnisvollen Kräfte von Leben und Fruchtbarkeit der Erde. Der natürliche Zyklus der Jahreszeiten wurde als göttlich gesehen und im Ritus abgebildet. In solcher von Wiederholung geprägter Theologie entsteht keine Heilsgeschichte, kein Konzept von Zukunft und göttlichem Geschichtsziel. Das Konzept einer

göttl. Mutter (die die Erde gebiert) ist verbunden mit dem einer göttlichen (od. ehrfürchtig verehrten, gottähnlichen) Erde. Hier wird die biblisch notwendige Trennung von Schöpfer und Geschöpf, Gott und Welt aufgehoben, der Begriff von Gottes Jenseitigkeit und seinem freien Erbarmen wird verloren. Die Vorstellung von Gottes freier Gnade,

auf der unsere Hoffnung gründet, wird so letztlich verunmöglicht. Hier wird deutlich:

Wenn wir Gott „Vater“ nennen und verehren, beten wir nicht einen männlichen Gott an (Hos 11,9), sondern den, der der Schöpfung gegenübertritt und sich frei ihrer erbarmt.

Jede semitische Religion im Nahen Osten hatte Göttinnen, nur Israel nicht (auch gab

es überall ein weibl. Priestertum, nur in Israel nicht!). Das zeigen auch die Personen-

namen, die sich aus dem theophoren 😊 auf den göttlichen Namen weisenden)

Element und einem Wort für Vater, Mutter, Bruder oder Schwester zusammensetzen.

Im Hebräischen gibt es viele Namen, die „Vater“ enthalten, aber keine mit „Mutter“:

Abijah („mein Vater ist Jahwe“), Joab („Jahwe ist Vater“), Eliab („El ist Vater“), Abiel

(„Vater ist El“). Personennamen mit der Aussage „Meine Mutter/Schwester/Königin

ist Jahwe“ kommen nicht vor! Von den 55 hebräischen Namen, die sich aus Jahwe

und einem Verb zusammensetzen, zeigen alle die maskuline Form des Verbs.

Daß Gott biblisch Vater und nicht Mutter ist, sichert so seine wahre Transzendenz 😊

Jenseitigkeit) und die wahre Gnade. Die irdischen Verhältnisse veranschaulichen es:

Die Beziehung zum Vater ist geistiger, indirekter, sie muß gewonnen werden;

die Beziehung zur Mutter ist zunächst leiblich vorgegeben, direkter.

Das Ergebnis ist klar: Gott können und dürfen wir nicht im Ernst als Mutter anrufen.

Die ganze Offenbarung steht dagegen. Wer Gott trotzdem als Mutter anruft, schafft sich

seinen eigenen Götzen. Wenn die „Bibel in gerechter Sprache“ für Gott lauter weibliche

Namen oder Titel einführt („die Ewige“, „die Weingärtnerin“ etc.), verliert sie gerade das

Besondere der bibl. Offenbarung, und sie verliert die besondere Mischung aus liebevoller und freier Zuwendung des Vaters samt dem Respekt vor seiner Autorität, wie sie Paulus

so perfekt in Eph 3,14–21 zusammengeschaut hat. Die Freude am „Abba, lieber Vater“

(Röm 8,15; Gal 4,6) bleibt uns nur erhalten, wenn wir den Text unverändert lassen.

Pastor Dr. Stefan Felber